Cook dinner by formula, not recipe

by Tracy Grossmann

I think we tend to view people who develop recipes as sitting in a lab, using beakers and grain-measuring tools, precisely doling out the exact amount needed for perfection. If the recipe calls for 1/4 teaspoon and we fudge it up to 1/2, well, the whole thing might just collapse.

In reality, most of our recipes come from a time when people dumped, poured, and stirred in the same ingredients to hone their favorite dishes, learning over time to look for that one tint of yellow that says the pasta salad has enough – but not too much – mustard, or the way the dough feels under-hand which says it has enough flour and kneading. The recipes gained from these interactions were most likely cajoled by a daughter or daughter-in-law, sitting on a stool in the kitchen, pen in hand, asking how in the world this or that dish was created.

A recipe is a guide, not a master

My husband’s grandma is known for her potato salad. One day, early on in our marriage, I determined to learn how she made this much-loved dish “her way.” One day, as she prepared it for an upcoming picnic, I stood by her side and asked her the ingredients and amounts, taking careful notes on each step in the process.

She measured nothing.

Wanting to have accurate measurements so I could recreate it perfectly, I asked her. And the answer was “Oh, I don’t know, honey, about this much.” So my little note card, that started out in list form, ended up with a drawing – a rudimentary bowl, three swirls in the center to signify mustard; one small blob to show how much relish relative to the spoon. I didn’t know how to quantify three swirls of mustard in tablespoons, so swirls it was.

My college roommate told me a story of when she was trying to get a recipe out of her grandma. Every time she mentioned an ingredient, my friend would say “Well, how much of that?” and she would reply “Oh, a handful or so.” Everything was a pinch, a smidge, a handful. One time she said “about a mouthful…” and my friend, from that day on, wondered how in the world you measure a mouthful…

I really think that cooking is more flexible than we are made to believe. Now, don’t get me wrong, I am not talking about souffle’s here…and I’m not talking about how to make something perfectly. I’m talking about real, down to earth, food-on-your-dinner-table cooking. We can all relax just a little bit, because honestly? The vast majority of recipes were handed down from grandma’s counter rather than through the science lab.

Sure, there are complex processes going on in our recipes, (for example, this in-depth article about sugar from Fine Cooking) but remember that for generations, we just knew by heart that adding too much flour would make the dough heavy, and a pinch of salt saved a dish from being too flat. And that learning- that deep knowledge -just came with time.

Get to know the cast and their roles

Like the many elements in a great play, ingredients come together in a dynamic way to make a great dish. Over time, one ingredient modification after another, you can start to learn how things like fats, sugars, starches, and proteins affect a dish.

You’ve just got to begin by thinking about what role an ingredient plays in a dish.

- Some are main characters (not much of a potato salad without the potato…)

- Some are supporting roles (the relish, the mustard, the mayonnaise). If these are taken out, they really need to be replaced by another actor that works in a similar way.

- Some are extras (onions, eggs, sugar) You can leave these out or add others in. They are not necessary, but they add depth and dimension to a dish.

- The costumes: Flavors are interchangeable without effecting the substance or the form of the dish, but you can’t put a suit of armor on a fair maiden and expect it not to change the story. In the same way, certain flavors make you think of Asian food, others of Mexican dishes. Flavors can be switched out, but remember not to go over the top (or under dress!)

I really think that Simplified Dinners helped me learn this way of thinking about cooking. I had always thought of something like Grandma’s Potato Salad Recipe as a standalone recipe, to make a one-off dish. But really, that same formula (bulky starch base, mayo-based dressing, extras for fun) can be used to make pasta salad (pasta, mix in a dressing, add in some extras) or even a vegetable salad (switch out your starch with a veggie like broccoli, mix in a dressing, add in some extras). Or maybe I keep the same potato salad, and just change the costume and the extras, and end up with a Bacon Ranch Potato salad. It’s the same story line, with different characters.

Be courageous in the kitchen

Sure, to change a recipe you’ve got to have a bit of courage – it takes a bit of a leap to modify things. Sometimes you aren’t going to know what exactly an ingredient does in a recipe until you forget to put it in. When you get to really know a recipe, when you’ve made it a number of times, you start to know what it needs. The bread recipe that I’m using right now, for instance, is so super simple, it’s almost funny that I ever forget to add something. But I do. And since I’ve made it a hundred times before, I can tell “oh, man, I forgot the salt!” or “wow, there is no oil in here, it’s sticking to everything!” And that just takes time and getting to know a good recipe like an old friend.

It’s been 13 years since I first wrote down grandma’s recipe for her family-famous potato salad. Over the years I’ve tweaked it and changed it, and am now a confident mustard-swirler, without regard to whether it’s three or four times around the bowl. That recipe has become an old friend, along with many others. And when I go to teach my kids that recipe, I’m sure it will be the same discussion as grandma had with me so long ago “I don’t know, honey, about this much.”

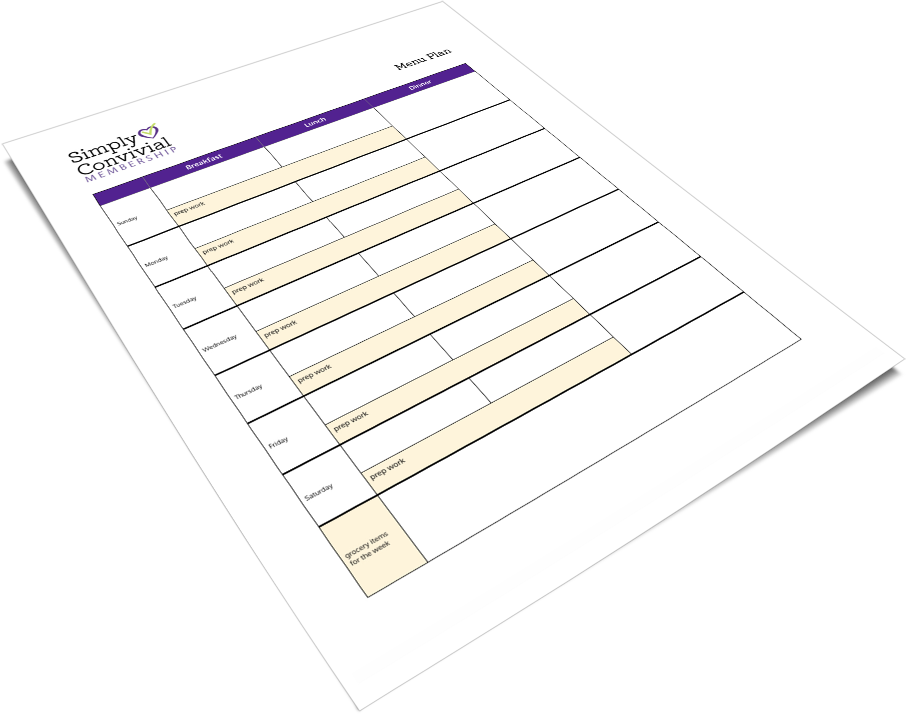

This menu plan template and master pantry resource will help streamline your kitchen.